Chapter

15: The Voice of God 031725

When

the tail end of “A” Company of the Black Lions (2/28th) trickled into LZ

X-Ray, artillery officer Hearne and other key officers had already

joined Lazzell, at the spot where the command bunker was going to be

dug. There they stood, listening to Lazzell flap his jaws when he should

not have been calling for a meeting in the first place. Instead, he

should have just finished working Hearne's behind off, having him call

down multiple barrages of artillery on previously registered points

around the clearing. Napalm and cluster bombs should have also been used

to clear away any ambushers and their equipment. Yet when I landed hours

later, the area was as pristine as ever. After the prepping , he should

have had his soldiers double time around each side of the large clearing

toward the north end, with the speed and urgency of an air assault. Soon

after that, Lazzell should have been walking the perimeter, himself,

making sure defensive positions were being dug in the correct locations.

They also should have begun digging in immediately. The two trailing

companies of the Black Lions should have been ready to double time into

position behind the Rangers (1/16th), instead of being allowed to linger

far behind. There had been an abundance of warnings recently, to

indicate that nonchalantly strolling into LZ X-Ray could be suicide.

Triet's sappers were keeping him abreast of when Lazzell would arrive at

LZ X-Ray. I talked about that in the last chapter. Yet, it's obvious

from reports and maps, that Lazzell was taking a very cavalier attitude

toward the entire march, from LZ Rufe to LZ X-Ray. Sergeant Murry,

himself, later verified that no one was told to dig in when his men

first arrived. Instead, the men were allowed to rest and eat lunch. This

means that they were allowed to fall into a much more relaxed state of

mind than should have ever been allowed. Boxes of machine gun ammo were

scattered around where they were not in easy reach of the gunners. Some

men started writing letters home. Some took naps. This type of relaxed

state would never have been allowed by Dick. Yet, it would be wrong to

blame what happened next entirely on Lazzell. The buck did not stop with

him. He just did not know what he didn’t know. He had convinced himself

that he had arrived as a commander and there was absolutely no one to

show him differently.

When the attack started, Hearne was standing in a circle of key personnel, called to meet together by Lazzell. Suddenly sporadic gunfire could be heard in the background. Those first shots were fired by Triet's tree snipers. They should have been burned up in the prepping, but that never took place. Now, Triet was able to telephone orders to those snipers to start shooting Lazzell's men in the clearing. He was able to telephone them, on that same como wire, which also should have been destroyed in the prepping. Just before that shooting started, Triet's machine gunners were ordered to move into previously designated positions around the perimeter. They held their fire until hordes of uniformed conscripts could be funneled from ox cart trails into shallow prone shelters just in front of them. These had been dug earlier. The main purpose of those tree snipers was to force the American's to keep their heads down until the conscripts could be moved into position. Launching the attack was made much easier by the lack of prepping but also by grunts being allowed to settle into a relaxed state with no urgency to start establishing permanent fortified positions. It was obvious to Triet that there would be no further prepping because those big slow moving Chinooks blocked the flyway near the clearing, as they started arriving with supplies. These conscripts moved into positions just as they had practiced several times before. That's what left all those many foot prints which point man Donnie Gunby had spotted earlier. Neglecting to prep the area was Lazzell's gift to Triet and Triet wasn't about to waste such a gift.

Once Triet's

snipers were given permission to start firing it didn't

take long for them to realize that these Chinooks made much

better targets than individual soldiers in the clearing. The Chinooks

were big, and they were slow. They were slowed even more, because they

had webbing dangling from under their weather-beaten bellies. That

webbing was crammed with all

sorts of resupplies. The diversion, these Chinooks offered snipers,

probably saved some American lives. Only one man in the “A” Company of

the Black Lions was killed in the clearing by a sniper. His name was

Lloyd Wohlford. His friend, Spec-4 Canute was lying beside him when he

was fatally shot. Canute immediately drew sergeant Bivens’ attention to

what was happening. The sergeant took it upon himself to have his squad

break formation with the rest of his company and move closer to the

protection of the wood line. Others along the entire length of “A”

Company followed their lead. Sergeant Bivens’ unilateral decision to

break formation and move proved one thing. It proved that he understood

that the most important part of his job was looking after his men.

Personally, I do not believe this was understood by most field

commanders in Vietnam.

The enemy attack was more concentrated on the northwest corner of the

perimeter, where several ox cart trails converged into the clearing. I am not going to give great detail about the

battle. In his book, David Hearne has already given many great details, which he

took from eyewitness accounts of the people who were there. Sergeant

Murry was in the heaviest

fighting on the north end. He also recanted many details of this battle

in his book. The name of Hearne's book is "June 17, 1967 - Battle of Xom Bo II". Murry's

book is entitled "Content With My Wages A

Sergeant's Story". Sergeant Murry's two machine gunners, in second platoon

were among the very first exposed to the opening attack. They were first

hit with machine gun fire and rocket launchers. Then whistles were blown

signaling for the machine gunners to halt their fire and the conscripts

to move out of their shallow trenches and attack the perimeter. Jose

Garcia heard the NVA conscripts coming toward him before he saw them.

First platoon was to Garcia's front hampering his men's ability

to return fire. However, Sergeant Murry thought quick and was

able to reposition his two machine gunners, Jose Garcia, and Bob Pointer

on the left flank where a gap existed between “B” Company of the Black

Loins and “A” Company of the Rangers. When Jose opened up, he was

answered with an enormous volume of return fire. I say again that the

lack of prepping

around the clearing made it much easier for the enemy to maneuver

because there were no downed trees and branches that a

good prepping would have created to obstruct their advance. The enemy

was afforded much

easier access to predetermined points around the perimeter. Murry lost

most of his squad but he and Jose and Bob along with the grunts in first

platoon repelled the viscous main attack on the north side. Black pajama sappers, who were skilled at probing for holes,

rose from their prone shelters when the firing subsided. Then then

started herding those conscripts still standing and those reserves still

pouring in around the flanks. Machine gunners Jose Garcia and Bob

pointer had miraculously halted a breach in the perimeter which could

have otherwise over-run Lazzell and his headquarters people. Now, more

and more arriving conscripts poured in and were led around Murry's

flanks to probe for softer spots in the perimeter. As usual, most of the Americans shot over their enemy's heads,

but not so with Captain Ulm’s B Company.

Captain Ulm's Company of veterans held down the east side of the

perimeter and they definitely did not shoot high nor did they waste

ammo. Charging

conscripts were riddled with bullets so efficiently that any survivors

didn't take long to decide to probe elsewhere. Triet's conscripts had a

much easier time on the south side. American return fire was much lighter there, because there

were only thirty Americans covering an expanse of the perimeter which

should have been covered by entire company. I mentioned this fact

earlier.

Lazzell should have redirected Hearne's A Company of the Black Lions to

cover that side of the perimeter as soon as they entered the clearing.

Instead, he allowed them to continue marching single file toward the

north end of the open clearing. Now, The Americans on the south side

were out in the open and facing an enemy who outnumbered them at least

ten to one. The NVA advanced almost nonchalantly into that south end of

the clearing, murdering the wounded, and taking souvenirs, as they went

along their way, unaware that on other sides of the perimeter, their

comrades were not faring nearly as well. This is proof that fire fights

in Vietnam had some very strange aspects to them.

Meanwhile back at

Lai Khe, during the attack on LZ X-Ray, my squad was just finishing up a

nice hot lunch and returning to our perimeter bunkers for a refreshing

afternoon nap. I had already positioned my nap time spot behind some

sandbags, so a sniper could not zero in on me. Milliron was still

state-side and Bowman was also gone on R & R. The ever-faithful Walker

was there, as always. Unfortunately, my nap time plans were soon

interrupted when Bartee returned from a briefing at command center.

Moments after returning, he gave us orders to saddle up, and before long

another unit showed up to relieve us of perimeter guard duty. We

followed Bartee down the dirt road which led to the mess hall tent,

where we had just been served lunch. Other groups of men in my battalion

were already congregating around a line of "deuce and a half" trucks.

Some had already started climbing into the back of empty trucks. It

wasn't long before the trucks were loaded and started pulling away,

heading through a grove of rubber trees, and toward the air strip. While

riding to the air strip, Bartee explained that the Rangers (1/16th) were

under heavy attack and needed our help. When we arrived at the air

strip, a line of helicopters were already waiting for us to load up. We

were down to seven men, in my squad, and low on new recruits in the

unit, as a whole, but never mind that. Two companies of my battalion (my

B Company and Mac McLaughlin's C Company) jumped off trucks and filed

down the right side of that line of Huey helicopters. The general

feeling was, that we had the best "ole man" in the entire division and

we could handle anything the enemy would be able to throw at us, as long

as some ignorant lieutenant didn't get in our way. That was the general

feeling. However, I would soon discover that my own feelings were

starting to dance to a very different tune on this particular day. The

chopper's engines were running. Their rotor blades were turning slowly.

It was “hurry up” and “wait”, and “wait some more”. We knew the drill

and would only board a chopper when told to do so. While waiting, some

guys took this opportunity to nervously check their gear. Some left our

lines to walk over to several stacked crates of ammo, hand grenades and

C-rations. Most of us stocked up on such stuff long before we thought we

might need it, so we just sat in the red airstrip dirt, leaned back on

our ruck sacks, and waited. Standing a very short distance away was the

tall lanky Mac McLaughlin. I didn’t recognize him as being the same

new guy whom I had been envious of, while he was digging in next to me,

several months before. That day was a thousand years removed from the

thoughts in my mind on this day.

Then it happened. I watched the door gunner in the helicopter directly

in front of me jump out and walk toward the rear of his chopper like he

had probably done hundreds of times before. This time he walked directly

into the whirling blade on the tail of the chopper. He was killed

instantly. Within a few seconds medics responded and retrieved his limp

body. When it happened, those of us waiting to board choppers did not

flinch. Truth is, most of us were too familiar with sudden death to do

that. However, I and several other veteran's whom I interviewed years

later still remember. Mac McLaughlin was one of those guys. It’s

probably a good thing that I did not recognize Mac standing so close

beside me sporting sergeant stripes while my sleeves were now bare.

In the past I had waited a

lot, but this time it was different. The longer we waited to board our

chopper, the more time I had to think. The more time I had to think the

stranger this certain feeling became. There was no logical reason for

what I was feeling. We were probably going to be flying straight into a

living nightmare. Maybe part of the reason for this strange feeling was

having seen that door gunner get killed in such a senseless way. No

matter what triggered it, I would have never in a hundred years expected

to be feeling what I was feeling. I was euphoric. That euphoric feeling

was further buoyed up by the sound of a recent rock song by "The Byrds".

That song was playing over and over in my head. The name of that song

was "Hey Mr. Tambourine Man”.

Had I finally lost my ever lovin mind? I was actually feeling

a tidal wave of upbeat emotional energy. How could I be experiencing

that at a time like this? Instead, I should have been feeling at least

some anxiety over the very real prospect of dying. We knew for sure that

we were flying into a hot LZ. I knew for sure that I was carrying a

worn-out M-16, which couldn't hit the side of a barn at fifty paces.

However, my mind was having none of that. Instead, it was embracing a

feeling which was totally new to me. I can only explain that off the

wall sensation in the following way. You see, there was a much greater

fear than combat, which had been taking over, little by little, since

joining my unit and even before A.I.T.. I had no outlet to numb this

growing fear. I never drank. I never smoked and I never complained about

anything to Sergeant Bartee, or anyone else, for that matter. I just

tucked things down, inside, and went along to get along. I was

convinced, that I was powerless to change anything anyway, so why try?

From those first days, shortly after basic, and starting during the

training in A.I.T., I had learned that excelling didn't buy much

respect. In fact, it seemed to do just the opposite in my case. After

finishing A.I.T., I was not promoted to P.F.C. as 99% of the others

were. Why was that? Was it because my sergeants had to stay up all night

looking for me, during escape and evasion training? Maybe. Or was it

because I had refused to buckle under, when given the third degree,

about not signing up for Officer Candidate School. Maybe. I never really

figured out the reason. However, I assumed that it was one or the other.

It could not have been for poor performance, because I graduated A.I.T.

at least in the top ten. One sergeant told me that I would have

graduated first in my class if I had only run the mile instead of

walking it. There was a reason for not running that mile. As the

smallest kid in my junior high class, I used to have to run from

neighborhood bullies all the time. By the time I turned eighteen, I had

worked out enough to face off with every single one of those bullies. I

told myself afterward that I would never run again unless I was running

of my own free will.

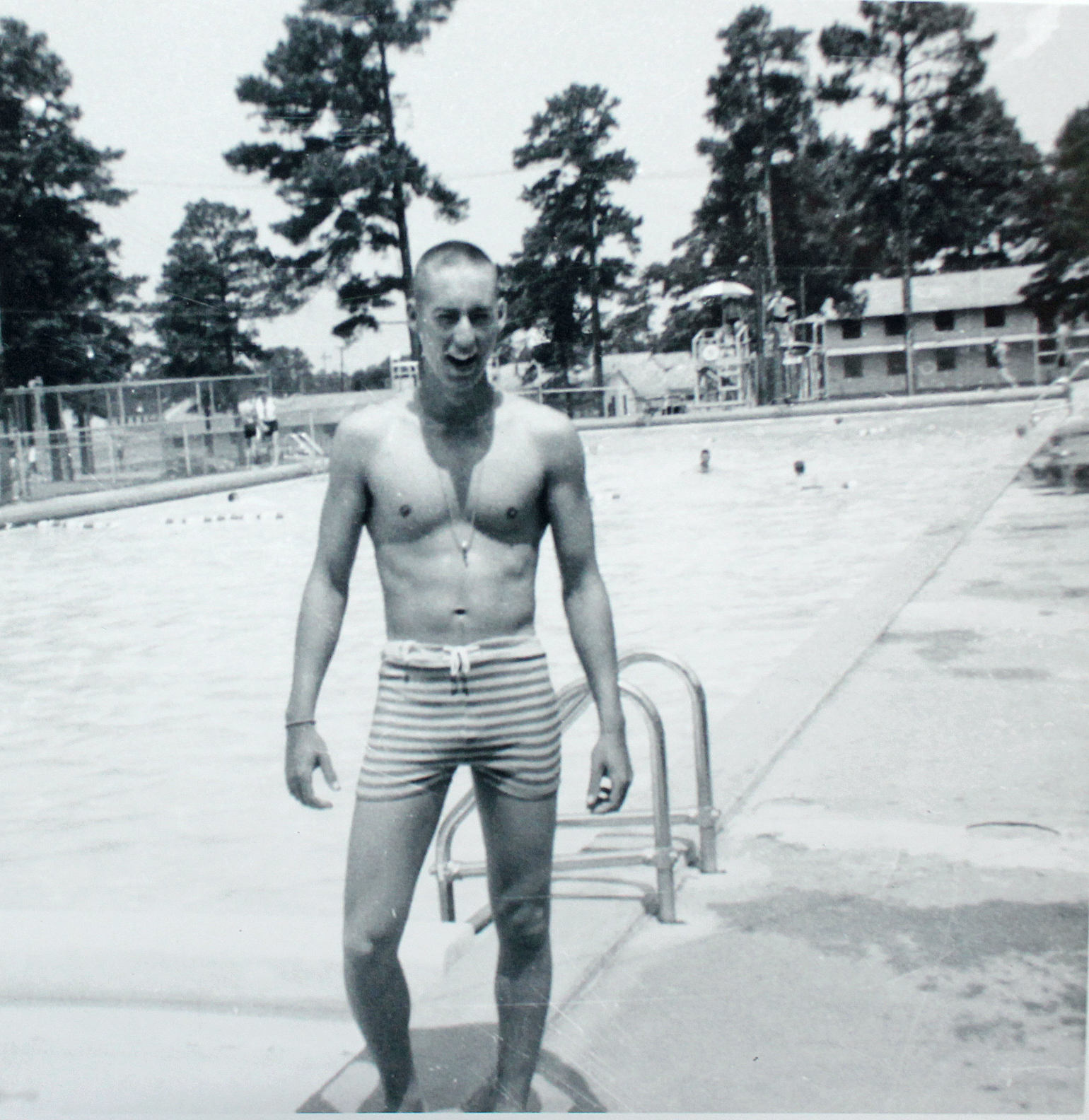

Wayne Wade - Fort Jackson June, 1966

The most recent

occurrence, fueling what I now realize were passive aggressive

feelings, was the article 15. It didn't bother me much at first. Yet,

afterward, in the days since, I could feel a kind of slow smoldering

deep inside, with the misdirected object of that growing anger being

Captain Brown. Though he was an actor in a minor incident, he was also

somewhat of a last straw. My perfectionist mind was now causing me to

close off more than ever. The distain which I felt for most of the

current leadership of my unit and the military in general was

overwhelming. The damage that anger was causing to my sanity seemed,

however, almost sweet to the taste. I knew my day would come. I would

get even. In the meantime, one thing I knew for sure. I knew, if I

wanted to survive my superiors, I needed to be careful. Interestingly,

that fear which I was feeling was much more potent than the fear I had for that Cong hiding in the jungle. My fear

was an overwhelming fear of “good ole Uncle Sam. That child molester

had been allowed to expose me in my last year as a teenager to an X

rated environment. At the same time, he was telling me that I was too

young to vote. Now, however, what could I do against such a powerful

enemy. Besides, I loved my country, but I very much hated the people

running it.

We boarded our chopper and started lifting off the ground. The sky was a pale blue, and the landscape below was dotted with patches of rubber trees around Lai Khe. Soon, rectangular outlines of rice patties could be seen. They hugged muddy brown riverbanks, which snaked through the countryside. More emerald, green jungle soon appeared, as we flew further northeast toward the beleaguered Murry and his Rangers and David Hearne and his Black Lions. It was only a fifteen-minute ride, but it was the most exhilarating ride which I have ever experienced in a helicopter. Other lines of Hueys were all around us in the air. The combined beatings of their main rotors made a noise, which gave rhythm to that euphoric feeling inside me. No Vietnam vet will ever forget the distinctive sound made by a Huey's main rotor. That sound will always send a shiver up our spines. On this particular ride, however, their rhythmic beats were joined by that other strangely euphoric sound. It was that song "Hey Mr. Tambourine Man", by the Byrds. I had first heard that song, while listening to the Saigon radio station, on that small radio, which I carried in my ruck sack. Now, it was repeating itself again and again in my head. As I look back more than fifty years later, I can see myself sitting with legs dangling out the door of that Huey. As my legs dangled from that chopper I am also sure of something else which was happening on June 17, 1967. While those stringed instruments of the Byrds were playing in my head to the beat of those chopper blades, I really was well on my way to losing my "freaking" mind.

It had been a long and terrifying afternoon for forward observer Hearne and an even more terrifying one for Murry, and his machine gunners, Garcia, and Pointer. It had been just as terrifying for many others, as well. Men had been killed all around Murry, Garcia, and Pointer, since they experienced the brunt of the attack. Miraculously they survived. However, when the shooting was over, only six men in Murry's platoon were fit for duty. Lazzell had gone air born in his bubble helicopter early on. He wanted to place himself in a position to better coordinate artillery and air strikes, but like everything else this guy did, that was a mistake. The background noise from his helicopter and the battle, itself, hidden from view by the triple canopy jungle, prevented him from affectively doing what he was trying to do. For all intents and purposes, when Lazzell went airborne, he became just another spectator, who could little affect the battle going on below him. Come to think of it, that may have been a good thing.

My ride would have become a death trap if we had started receiving incoming fire as we landed. Fortunately, The main attacks were over when we got there. When we reached the LZ, choppers in front of our own banked toward the clearing and swooped low over the trees to lessen the chance of taking a hit. Centrifugal force was the only thing holding me to the floor of my ship, as our bird banked to follow the one in front of it. We made our final approach, and our pilot was good. He brought the Huey to within six feet of the ground. In less than four seconds everyone in my squad was running for the wood line. Many years later, Dick said that he was already on the ground directing traffic, when my B company got there, which did not surprise me. I immediately dropped my ninety-pound rucksack as soon as I exited the aircraft. As I ran, I could see, to my left, in my peripheral vision, soldiers dragging black body bags, filled with the limp bodies of young Americans. Those bags were being added to a line of others near the northwest side of the clearing. That line was already twenty to thirty bags long. Inside the tree line I came face to face with only one defender, from the ambushed Rangers (1/16th). He had superficial cuts on many parts of his body, from flying shrapnel. Immediately, he warned me that he had been receiving sniper fire from one of the big jungle trees about twenty meters to our front. About thirty seconds later mortar rounds started falling to our right side. One landed no more than ten yards away. The other soldier and I hit the ground together and crawled behind a large termite hill, which did not offer much protection against flying shrapnel, but it was better than nothing. Cries for medics soon came from our right side. Michael Morrow, an RTO in the Black Lions Battalion, was killed by one of these mortar rounds. It was the largest mortar attack of the day. I would not find out until over fifty years later that this mortar attack had wiped out an entire squad in my platoon. Captain Brown's RTO, Fred Walters, told me years later that Porky Morton, Bianchi, Schotz, Ruiz and Lemon were among those wounded in that squad. They were wounded so badly, that they never returned to the unit.

I had also been raised by a father who taught me a little about navigating the woods. His lessons contributed greatly to my survival. It’s true, that my father put no emphasis whatsoever on encouraging me to become involved in sports, as other fathers did. It’s also true that involvement in these school activities helped give my classmates a head start over me in the civilized world. However, the world I was in now was not civilized. I don't think that I would have survived this uncivilized world to return to that other world, if not for those alternative lessons, which I learned from my father. My father had been the one to teach me how to navigate the woods at night with a compass and not the Army. Those lessons learned early meant that I had no problem holding the compass, shooting a bearing, and continually counting paces, with no help from anyone else. It would have been nice if Milliron and Bowman could have been there, but I didn’t need them to do my job. The distance to the first check point was around 800 meters. The second check point would be almost twice that. This was not a short security patrol. It was more like those patrols assigned to recon platoons and was by far the longest squad patrol which I had ever run. There is one more thing worth mentioning. It was something which was hugely important to the survival of any patrol. That something was squad leader, Sergeant Bartee. Lately, I was able to count on Sergeant Bartee much more than when he first showed up to take over the squad. He trusted me to do my thing, and I could trust him to do his. Today, without Milliron and Bowman's help, it was more important, than ever, for that to happen.

Looking back now, after analyzing various "after action reports" it was apparent, that there was a lot of signs indicating a heavy enemy presence still in this area of operation. The enemy unit, which attacked Lazzell at LZ X-Ray, was also the same unit, which attacked Alexander Haig near the Cambodian border, on April 1. That was only two and a half months ago. Now, this same unit had just mounted a full-strength attack over sixty miles closer to Saigon. Something wasn't adding up. That was a big clue that decimated units like the 271st were not retreating over the Cambodian border every time they got shot up, as we naďve Americans believed. Given time constraints, I realize now that this was not plausible. How could Thanh have Triet do that, and yet, show up again, so soon, sixty miles further south? It seems to me now, that our American politicians where very susceptible to the very smooth Svengali of the communists. Many very smooth but false tactical narratives about our enemy were fed to our American news media and then passed on to influence many of our politicians. Those viewpoints not only seemed to give too much unrealistic credit to the enemy's fighting ability, but also way too much virtue to the leaders of their side of the conflict. In this case, there simply would not have been enough time for Thanh to have reconstituted the 271st, transforming raw recruits into what is sometimes described as the "fabled" and "storied" veteran jungle warriors. Here is a much more plausible picture of what was really happening. The NVA who filled the communist ranks were "ravaged conscripts", some as young as 12 years old, who would be very fortunate indeed, to survive the criminal war tactics imposed upon them by their communist masters. After the battle of Ap Gu, the surviving conscripts of the 271st kept moving south. Their ranks were replenished, on the march. They took temporary breaks to resupply and rest along the way, in the numerous base camps, scattered from Cambodia to the outskirts of Saigon. These NVA forces were not "long time" veterans, as we supposed, but instead, were "doped-up" brown and green uniformed teenage conscripts, whose jungle fighting skills were limited to, not much more, than a ten-minute lesson, on how to fire an AK 47 or a handheld rocket launcher. They were also given a very short lesson on how to respond to a whistle or a bugle, so their hard-core communist cadre could more easily herd them into their suicidal death charge positions. My guess is that anyone refusing would have been immediately shot in the head.

That message made me freeze, in my tracks. I then slowly turned, and just stood staring at Bartee, which broke the one cardinal rule which I always obeyed. That rule was to never take my gaze off the jungle to my front. Bartee was fifteen paces behind me. He knew I had something important to say, so he kept walking toward me, until he was within whispering distance. His radio man followed close behind. The rest of the squad remained motionless where they were before he started walking toward me. As he closed the gap between us, he never took his eyes off mine, and he never uttered a word. When he stopped, his face was five feet from my face. He just stood there as quietly, as if he was a church goer waiting for the praying to start. In that instant, as I stared into his handsome twenty-six-year-old countenance, his features became so ingrained in my mind, that I can still see them today, as clearly as I did then. He was five foot nine with sandy blonde hair, blue eyes, and fair skin. I can also see the droplets of sweat "beading up" on his face and dripping off his nose and chin. He had a very compliant expression, which said that he was willing to receive whatever I was about to say, with the same respect due the voice of God. At this instant, with all his faults, our squad could have asked for no better leader than Sergeant Bartee.

"They are just in front of us", I whispered in a very matter of fact tone. When this communication was given, Bartee's trusting demeanor never changed. There was not a hint of doubt in his face. He had just heard the gospel truth and he knew it. However, I had no natural proof to confirm what I had just said. Without that proof, I am convinced no other squad leader in the entire First Division would have taken my word alone for it. Over the last few months, however, Bartee had developed the rare ability to trust me and the rest of his men, much more than before. You see, trust breeds trust just as suspicion breeds suspicion. By now, Dick had laid a good foundation for that trust to grow down through the ranks. However, Bartee trusted me more than I trusted myself. If he had questioned my judgment this time, as he had done, when he had first become our squad leader, there would have been no pushback from me. In fact, I would have been the first to agree with any second guessing from him. Truth is, I had absolutely no proof that anything was out there. Yet, Bartee ran with my original unfiltered announcement. That announcement had come straight from my heart and Bartee acted on it before I had time to second guess myself. That was an amazing milestone in our working relationship. Looking back now, I realize that God had handpicked the one in a million lifer sergeant who would take me at my word. He had complete faith in me. However, the final decision on whether or not to continue our patrol did not rest with him.

There was little doubt that these were the NVA conscripts who had participated in the ambush of the 1/16th and the 2/28th on the 17th of June at the battle of Xom Bo II.

We stuck around LZ-X-Ray until the 23rd of June, along with Hearne and his Black Lions (2/28th) Infantry. Both battalions made company-sized sweeps of the area during the next three days but made no significant contact with the enemy. Knowing what happened a few months later, it is obvious to me now, that Triet stayed in the general area. He did not run for the Cambodian border. Our night ambush patrols could hear heavy enemy activity each and every night, while we were at LZ X-Ray. I am sure now that fresh conscripts were pouring in to reinforce his present hideout from other jungle hideouts nearby until his ranks were completely replenished. I don’t think Westmoreland ever realized that he was fighting a conveyer belt. On the morning of the 23rd of June, we were flown out by helicopters, just after the 2/28th was also air lifted out. The choppers took us on a twenty-five-minute ride to Fire Base Gunner 2. There we waited until afternoon to catch a ride in some C-130 fixed winged aircraft which flew us into Di An and a nice folding cot to sleep on that night. It was a great feeling to hear rain drops splattering off the roof of my tent instead of my plastic poncho. Yeah, everyone was taking a break, but it would just be a matter of time until Triet would try to do to Dick what he had done to Lazzell. Furthermore, his bosses didn’t care if they had to get ten thousand teenaged rice farmer conscripts killed to do it.

Chapter 16